Straight to Treatment After Jail? Do I Stick to My Guns?

Photo credit: cottonbro studio

Sometimes we can see the likely future: our Loved One returns to the shelter of home, hides away in their room, and simply doesn’t get the treatment they need to make progress with their SUD. Allies’ member HelenBo doesn’t want to see that happen with her son, who is struggling with heroin and other substances. What other housing options will he have upon release? As Laurie MacDougall writes, there are often more than we realize. At the same time, such transitions are critical moments for our Loved Ones. Having a list of specific housing and treatment options at hand—along with the CRAFT skills to communicate about them effectively—can make all the difference.

My son just had his 21st birthday in jail. He’s been there for just over 3 months. I have just started with AiR and have a lot to learn. My son is up for parole in a couple of months and has asked if I will allow him back home. I straight-out said NO and that I wanted him to go to rehab. Very controlling, I know now after completing some of the modules. He is a heroin user and also takes whatever else he can get. Our process has been going on for seven years; he’s never been in rehab and has completed detox a couple of times but to no avail.

My question is, should I let him come home, or should I stick to my guns? What I am worried about is him getting out and having nowhere to go and no support. I am going to call the prison tomorrow to see how they can help. But thought I would put it out there to see what you all thought.

Thanks,

HelenBo

Hi HelenBo,

Sounds like you’ve been on a long journey! What’s amazing is that you’re still in it, fighting to help your son. Not easy, but a testament to a mother’s resilience and the love motivating you to continue.

The dilemma causing you angst is what to do when your son is released from jail. On the one hand you do not feel he should return home unless he completes inpatient treatment (correct me if I’m wrong, but I think inpatient is what you have in mind). On the other hand, this choice might leave him homeless and without support.

When making this decision, you might consider two things. First, widening your thoughts on what constitutes treatment. Second, looking at the numerous options open to you and your son. It isn’t just a choice between letting him come home and leaving him out on the streets (or couch surfing). There are a whole lot of other possibilities for both you and your son to consider.

A broad array of recovery options

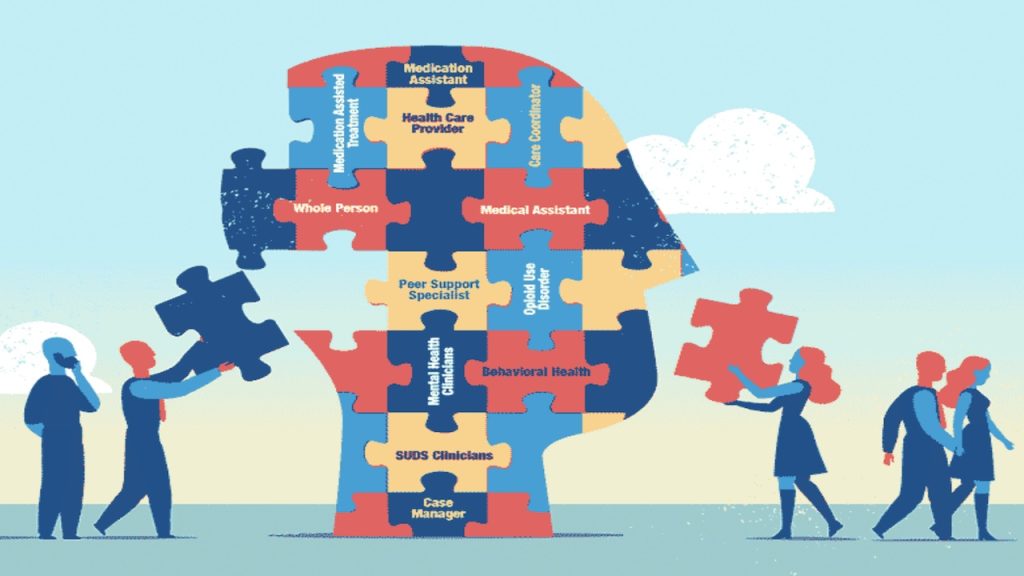

Another thing to consider is that if your son has been in jail for months and has not been using during that time, inpatient treatment likely won’t take him on as a patient. Nor would insurance be likely to pay out if it did. The wonderful thing is, inpatient treatment isn’t the only possibility. There are lots of ways to create an individualized program to support someone in their recovery. Here are just a few ideas to inspire thought:

- Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) or partial hospitalization day programs (PHP). Both of these are day programs and include much of what is offered in residential treatment. There are groups, meetings, counselors, skills workshops, psychologists, psychiatrists, etc. Many of these programs offer transportation. The patient lives at home and is still responsible for feeding themselves, finding a job, and all the other components of life. This is a means of getting support while continuing many of the routines and responsibilities of a normal life.

- Counseling.

- Medicine for both opioid use disorder (OUD) and for any mental illness or trauma.

- Support group meetings like NA, AA, SMARTrecovery, Life Ring, Wellbriety, etc.

- Exercise or body/mind practices: yoga, gong baths, Refuge Recovery, hiking groups, listening to music or playing an instrument, riding a bike, CrossFit, rock climbing, etc. Often you can find groups that offer yoga or meditation specifically for people in recovery, but it does not have to be limited to that. Adding activities that might be enjoyable and directing their focus to something productive can get them moving physically and simply feeling better. Doing so can also reduce the time they spend experiencing ruminating thoughts and add the vital benefits of increased social engagement. They do say that the opposite of addiction is connection, and engaging in these types of activities can help people become connected. Such activities don’t necessarily have to be designed for recovery, although of course they could be.

- Recovery housing. Many recovery housing facilities also come with services like counseling, an IOP, hiking and other group activities, and support to attend meetings together.

- Finding and moving in with a roommate.

- Is he religious? If so, then can you encourage him to get to his church, synagogue, or temple?

- Are there any activities that you and your son would enjoy doing together?

- Volunteer work—for example, at a local animal shelter? Animals and pets can be a connection and support for a person. Sometimes recovery homes have a pet living at the home that everyone takes care of; doing so can be very rewarding and comforting. Would it help if your son had his own pet?

- Acupuncture, chiropractic work, and other wholistic health offerings.

- Re-entry into the community and any services that he might need to help him readjust. In some communities there are workshops designed for just this sort of transition.

This is just a short list of “treatment” options. What about getting a little creative and giving your son a choice of things, you’re willing to support him with?

Of course, talking about this constructively will require some preparation on your part. Here’s a simple model you might consider:

Right now, coming home might not be the best option for you or me. But I have been thinking about options for support and resources to help move you forward. Would you be open to me sharing some ideas? You don’t have to follow through on any of them, just spend some time letting them run around in your head. Just food for thought.

If you get a yes then, follow up:

Well, there’s the option of a recovery home, with services like an IOP and counselors, and although it might not offer medicine, they may help you get to a nurse practitioner or psychiatrist who could prescribe it. I would be willing to pitch in to get you started. Maybe after a stay of six months or so, and consistency with these services, we could talk about what it would take for you to come home. But who knows, by that point you might not want to. You might want a place of your own.

Give him the time to think about everything you’ve said, especially if there is pushback. Make sure to reiterate that these are just ideas, and that he does not have

to follow through on any of them. Let him know you have confidence in the choices he will make. Ending the conversation with something like, “I’m sure you will figure out what works for you. I’m just throwing out ideas to consider. Let’s talk about this again later on.”

And later, check back in, “Hey, what are your thoughts on living arrangements and resources when you get out of jail? Whatcha decide?” Then listen, listen, listen. But once you have listened, seriously and compassionately, don’t be afraid to negotiate with him. Whenever you have something he wants, you’re in a great position to leverage that and determine what your needs are. For example: “I would be willing to help pay for some of your rent for the next six months if you are willing to stay consistent with visiting the counselor and taking your meds as prescribed.” It seems as a society we have lost the art of negotiation.

The good communication sandwich

What I have outlined here is the CRAFT communication skill of “sandwiching.” The steps are:

- Ask permission to share. If they say no, back off. This is a way to inspire the other person to think without “forcing” ideas onto them.

- If they say yes, great. Give them options, with no expectation that they will use those options. This inspires them to think and consider that they might have options they had not thought about previously. It gets them away from black-and-white thinking and reveals that there is whole bunch of grey too.

- Ask their thoughts on the options. This gives them ownership of the solution to their problems. You may have presented ideas, but they will determine which of those ideas, if any, they are going to utilize.

Your son might not choose to do things the way you would, or the way you think he should. He is going to choose what makes most sense to him. Just as you, in turn, will decide what works best for you.

It’s great that you are consulting his parole officer or the jail and trying to find resources available when he leaves. Sometimes, depending on the sentence, a person is actually not allowed to come home: housing is already decided for them. But resources take many forms. In addition to all of those I list above, helping him get on Medicaid right away could be vital. In any event, a good array of support resources laid out before him can be critical to his successfully adjustment back into his community.

I can understand the worry about him not having housing when he is released. But this is precisely why it’s so important for you to have information on other housing options ready for him: recovery housing, shelters, renting a room, possibly a group home for men, etc. He has options. They just don’t include your home at the moment.

It’s not just what we say that matters

And remember, the difference between an ultimatum and option is often just how it’s presented. No, you can’t come home, you have to go to treatment first! can be received as demanding and doesn’t give the person agency to choose for themselves. But compare that to: It’s not safe here at home. Here are some options for you to consider, and I’d be willing to reconsider you coming home if certain things are accomplished. Stating it that way gives our Loved One agency to make their own decisions, and an incentive to work towards a goal.

This is a lot of information, I realize. I do hope you find it helpful. The ideas I’ve presented here are just that, ideas. You are the expert on your family, and you’ll be able to judge what works best for you. I would just encourage you to get creative—and to practice those CRAFT skills! Your love for you son and your resilience shines through. Keep us updated on your progress. Wishing you and your son all the best.

Laurie MacDougall

LEAVE A COMMENT / ASK A QUESTION

In your comments, please show respect for each other and do not give advice. Please consider that your choice of words has the power to reduce stigma and change opinions (ie, "person struggling with substance use" vs. "addict", "use" vs. "abuse"...)