Understanding What Counts as Use Is Hard. Talking About It with Him Is Even Harder.

Photo credit: Shutterstock

An Allies member has been doing her homework: consulting Allies’ Learning Modules and making careful observations of her Loved One’s patterns of use and non-use of meth. But like most kinds of learning, her CRAFT observations have led to new questions. What counts as “using?” How can she encourage the change talk she’s hoping for, especially given his frequent anger? Allies’ CEO Dominique Simon-Levine reviews the precision needed and the promise latent in the CRAFT approach.

I am struggling with two aspects of applying CRAFT training:

1. My boyfriend uses meth. He goes through ten-day cycles, using and then being awake for a couple of days, sleeping for a day or two, then being angry (and scary) for a couple of days, and then normal for a few days. He is nice when he is normal and after using, but not before sleeping or when he’s angry. He no longer lives with me. I am confused about when I should consider that he “is using,” since the cycle is so long and complex. Can you help?

2. How do we draw out the change talk? How much change talk should we have before I mention treatment—or is it better to wait for him to ask for it specifically?

Thank you so much for sharing your story. You describe your boyfriend’s cycle with great clarity. You’ve observed him and understand the pattern in detail (exactly as Module 3 suggests). Being able to quickly size up where your Loved One is in the cycle tells you how to respond in the moment. And knowing all this can help you stay calmer and be less reactive.

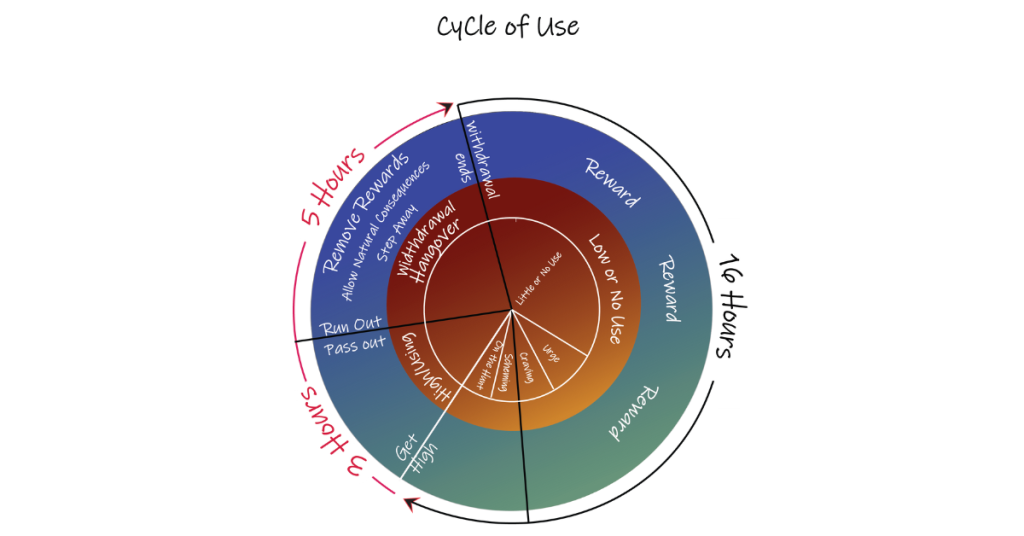

This kind of observation is the cornerstone of the CRAFT approach, and it’s already a strength you’re bringing to this difficult journey. In preparing my answer to your question, I asked a former meth user to describe his cycle of use to help us better understand it. Here’s some of what we discussed.

The bruising cycles of meth addiction

Recreational use of meth is possible; a person can stop after taking one hit, come down, and go to sleep. The problems begin when the user discovers that a second hit, and later a third, stop the drug from wearing off, the emotions from crashing, and sleep unnecessary. Eventually, a user’s relationship with the drug often moves from receiving desired effects to containing (or trying to contain) negative ones.

A binge ends when the drug runs out, or when taking more simply doesn’t work. The fallout often includes a host of uncomfortable, painful, or delusional sensations known as “tweaking” (symptoms described to me recently included hearing voices, getting itchy, being unable to keep still, dilated pupils, paranoia, and locking oneself in one’s room).

These are the conditions that often drive people to the emergency room. Meth stays in the system for several days, during which sleep is patchy, eating and drinking may cease or become erratic, and consequently, deeper delusional or psychotic states may occur. Eventually, the user comes back to some state of normalcy—until the next binge.

The cycle can differ according to the route of ingestion. Eating meth products tends to cause waves of tweaking/psychosis. Injecting it tends to produce the straight-line course I described above.

Now let me turn directly to your questions:

1. When is he “using”?

You’re not alone in feeling confused about this. Methamphetamine use tends to unfold in long, intense cycles—as your boyfriend’s case reminds us, it’s not as straightforward as a drink after work or a night out. With meth, we often see a “binge-and-crash” rhythm: using, no sleep, crashing, irritability, and brief moments of what feels like a return to baseline.

In CRAFT, “using” includes not just the active consumption but also the after-effects: being high, crashing, getting angry, withdrawing, etc… These are all considered part of the using phase because during those times your Loved One isn’t truly present or capable of connection and change. This is when (provided everyone’s physically safe) you disengage. Any attention, even negative attention, during these phases is a form of reward for the use behavior. Even being nagged by someone you love is rewarding! It’s much harder for the user to be alone with their choices.

So, when you ask yourself “Is he using?” think of it in terms of whether he is in any of these altered states. If he is, remove rewards—including yourself! — and allow for natural consequences. Now that you no longer live together, this will be a whole lot more possible. Still, it won’t be easy.

Those few days when he seems more like himself—rested, calm, and kind—are your windows. This is when you reward. Spend time with him, show warmth, and allow for connection. These moments matter, even if they feel short or fragile. Remember that these two sides of CRAFT work together: the more he enjoys those times when you reward, the more he’ll feel their absence when his using tells you to withdraw.

I recently met with a young woman in a similar situation to your own. Her boyfriend drank. They would get together at his place on weekends, an hour plus away from her home. If the boyfriend started to drink (they had agreed he could have a couple), she would hold out, say and do nothing. As her boyfriend crossed over the line from “a couple,” to more than a couple, she knew she should remove herself, but the whole weekend would be shot and she faced driving home quite a distance in the dark. Stuck, she would mention the drinking while he was drinking, or first thing the next day, and things would just fall apart, typically ruining the whole weekend.

What this example shows us is that the message needs to be clear, the line firmly drawn. How to put this into practice? I won’t pretend that’s not tricky. Could she plan to make day trips rather than whole weekend getaways? Is there a place in his house where she can remove herself for the evening and the next morning, until his hangover has mostly passed?

It’s also clear from this story how badly trying to engage during use can go. That’s another reason to withdraw. What would happen if she said nothing? What if she begins to engage him again only late afternoon the following day (provided he doesn’t start drinking again). Perhaps she leaves in the morning after spending the evening in that spare room. Wordless messages can say a great deal.

2. How do we draw out change talk?

This is such an important question. Change talk doesn’t need to be dramatic. It can be very subtle—a comment about how tired he feels, how he misses something or someone, or even a simple “I don’t want to live like this anymore.” These moments may not seem like much, but they’re signs of ambivalence and potential motivation.

You don’t need to jump in the moment you hear change talk. Let it sit. Let him hear himself say it. Then, after a few times, a few weeks, perhaps you prepare to gently respond. You might say something like:

“I hear you. It hurts to see you feeling this way. I’ve been gathering some ideas in case you ever want to try something different—no pressure, just when you’re ready.”

This opens a door without forcing it. Treatment doesn’t have to be the first suggestion. It could be an open meeting, a visit with a doctor, or even a walk together. You’re building a bridge, not making an ultimatum.

You are doing such meaningful, difficult work. It takes patience, courage, and love to stay steady in the face of addiction—especially with someone who can be scary and unpredictable during parts of the use cycle. Remember to keep yourself safe, emotionally and physically. If he becomes threatening, your safety comes first. The boundaries you set aren’t ultimatums; they’re lifelines.

You’re not alone, and you’re not powerless. Each step you take using CRAFT principles builds the possibility for change—in him, and in your own peace of mind. You are making a difference, even if it doesn’t always feel that way in the moment.

Lastly, I just want to say that all this isn’t fair. You deserve someone who is fully with you and well, someone you can spend all the time with you want. What we suggest with CRAFT are changes that can unblock the situation. CRAFT helps you clean up any inadvertent support of your Loved One’s use and suggests ways you can reward moments of non-use.

Remember too that it’s not forever. In clinical CRAFT situations, families are given 12 weeks. Fully half the families see results within six. What I’m saying is that CRAFT is a strong and dependable approach to what you’re facing. Even if it turns out not to lead you and your Loved One to a better place together, it will be of lasting value to you. Either way it will, I believe, make your options for the future much clearer.

Warmly,

Dominique Simon-Levine

LEAVE A COMMENT / ASK A QUESTION

In your comments, please show respect for each other and do not give advice. Please consider that your choice of words has the power to reduce stigma and change opinions (ie, "person struggling with substance use" vs. "addict", "use" vs. "abuse"...)